At the dawn of the millennium, DIY was all the rage. While it had been around for decades at that point, as early as the start of the 1900s, it was taking over a substantial market and weaving its way into other subcultures. Around that time, a new breed of DIY was beginning to form: the maker movement. It was niche and difficult to get into, until a little website called Kickstarter was launched in 2009. Suddenly, the maker movement (and other subsets of DIY culture) exploded.

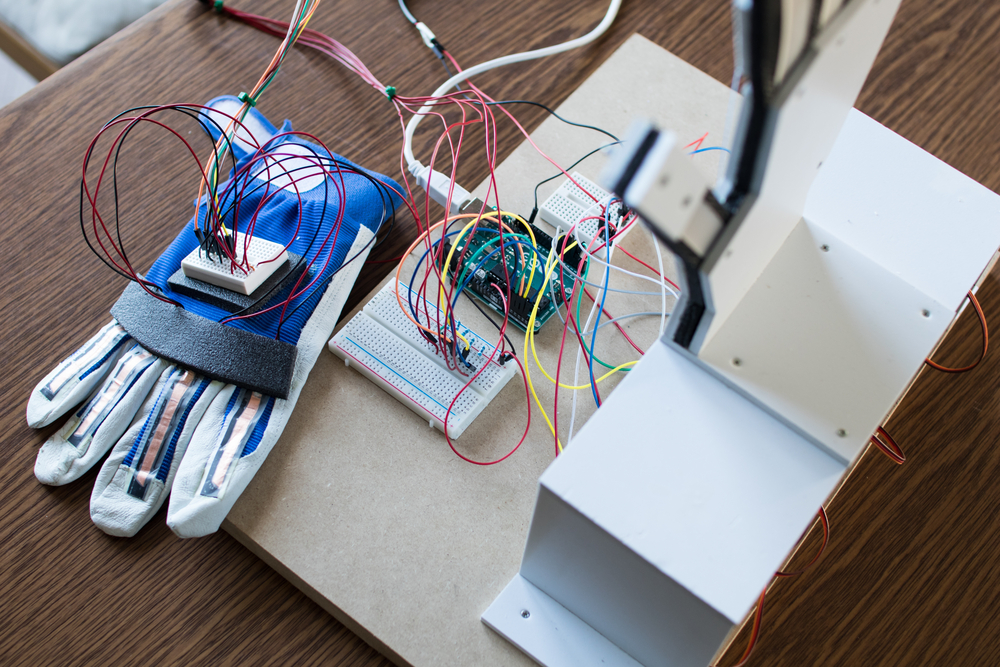

But what is the maker movement? It’s the technological side of DIY, with an emphasis on creating new hardware and tinkering with the old. There is some overlap with hacker culture, but hackers are more concerned with software rather than physical tech. Everything from robotics and 3D printing to metalworking and arts-and-crafts have their place in the maker movement. As the name implies, it’s about creating something new, rather than depending on the old. It’s about creativity and invention.

Obviously, none of these activities are new. Inventors and creative types have existed since the dawn of humankind. But the maker movement is the first time such a large and dedicated base is devoted to invention and production. Previously, inventors were considered odd and quirky, operating outside of normal trends. Now, they’re everywhere, and seen as visionaries. Revolutionaries, even. It all depends on who you ask.

That said, these modern inventors still face many of the problems their predecessors did–namely, securing funds. Not everybody is able to become an eccentric billionaire with a mansion full of strange devices. This is where Kickstarter comes in. An individual or group comes up with a product, technological or otherwise, and builds a prototype. They’re unable to convince any companies to buy and produce their product. Instead, they turn to Kickstarter, where anybody interested in their idea can invest in making it a reality and gain a few perks along the way.

Kickstarter was founded by Perry Chen, Yancey Strickler, and Charles Adler in 2009. It was an immediate success, with the New York Times calling it “the people’s NEA.” Reportedly, more than $4 billion in pledges have been made, across more than 250,000 projects. The very first successful Kickstarter was darkpony’s “Drawing for Dollars,” which exceeded its goal of $20 by 75%. Compare this to the most successful project, the Pebble Time smartwatch, which made over 4000% of its funding. Humble beginnings, indeed.

For the most part, it’s a win-win scenario. Inventors can promote their product and offer incentives for higher donations. Interested consumers can pay what they want, often getting an early version of the product in return. The inventors get funding, the consumers get the product. With Kickstarter’s policy of money only going to the host if the project is completely funded, there’s an extra layer of security in case of failure. And failures there have been- most notably, Central Standard Timing, which raised more than a million dollars before being canceled due to mismanagement.

Still, for every bomb, there’s one that manages to succeed. This has opened the door for hundreds, if not thousands of members of the maker movement to bring their creations to life. While this does saturate the market to a degree, it’s also allowed for some amazing advancements in just a few years. For example, coding was once a hobby for only the most dedicated computer nerds, requiring advanced knowledge of multiple programming languages. Now, kids can learn to code their own websites or games using toys or online tools. This, in turn, inspires a new generation of the maker movement.

Kickstarter and similar sites are not exclusive to the maker movement, nor are they the root source of the cause. Rather, the two coexist and work together to improve lives. Quite literally in some cases- a successful Kickstarter might help both the inventor pay their rent and result in a device that helps those with a disability. Yes, the platform has flaws, and the maker movement isn’t devoid of failure either. For every success story you hear, there’s at least a dozen more that have flopped.

The maker movement will only continue to grow over the next decade as new generations with interests in technology and creativity come of age. Some may even be so young as to not remember a time when Kickstarter was commonplace. There’s a new era of self-made millionaires out there, just waiting to be discovered. You just need to find the right link to their page.